In a recent study, researchers of the ELKH Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (KRTK) examined the host effect in the Olympic Games, which had previously been clearly established, from a new perspective. Previous studies have only examined the medal advantage of host countries aggregately and not separately, and their research fills this gap in the literature. Not only did they estimate the medal surplus associated with home hosting on the basis of total medals, but they also analyzed gender differences, which is also a novelty compared to previous studies. The paper presenting the study was published in the Scientific Reports professional journal.

It is often used as an argument in favor of hosting the Olympic Games that the advantages of the home field allow athletes from the host country to win more medals than usual. Many factors are attributed to the home field advantage, some of which have been empirically proven. The cost of participation is minimized, athletes compete in facilities adapted to their needs, they are more motivated in front of a home crowd, and judges' decisions are in favor of the home athlete or team in case of questionable situations. These factors, combined with an increase in government funding for sport in the run-up to the domestic Olympics, have led previous studies to indicate that the host country typically wins 1.8 percent more medals than its previous performance. This phenomenon is known in the literature as the host effect.

KRTK Researchers used sport-level data to control for heterogeneity due to changes in sporting disciplines over time. Previously, the literature has rarely used sport-level data for similar analyses, only aggregated observations at country level. In order to clearly identify the host effect, they used GDP per capita and population as control variables, which are two of the most important factors in the production of Olympic success.

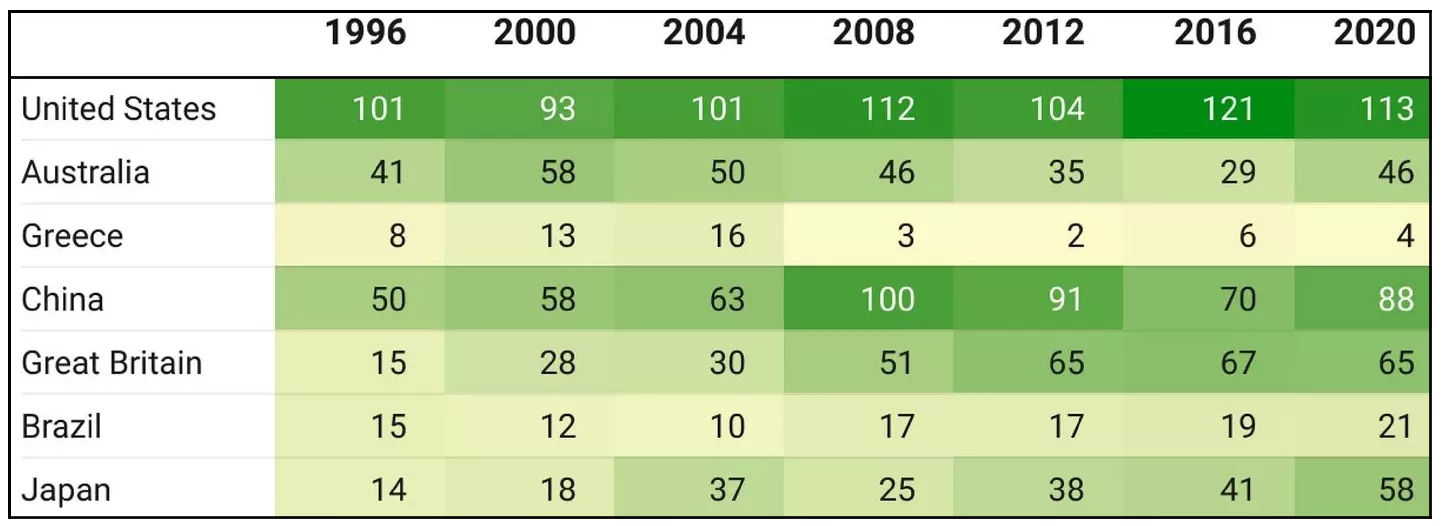

The baseline models without control variables show that the countries in the sample won more medals in their host events compared to the usual medal count. But when the estimations are done separately by gender, the results are quite mixed. The host effect is even less clear when GDP per capita, population and the communist bloc variable are added to the models. Based on total medals (without gender breakdown), significantly more medals are observed for only two host countries. But also only in two cases was the host effect significant when male and female medal winning was examined separately. A clear host effect was only found for the Sydney and London Olympic Games.

The main conclusion of the study is that in the future, the potential for outstanding national success should be used cautiously as an argument for hosting. As the study has shown, in terms of the number of medals won, only a few countries have clearly benefited from hosting the Olympics. However, if a country chooses to host the Olympics and intends to capitalize on the home field advantage, it should prioritize sports where such an advantage truly exists.