The bones that the researchers of the Research Centre for the Humanities reported on in the first stage of their scientific research may belong to the close family of King Andrew I of Hungary, who founded the Benedictine monastery in Tihany, and perhaps even the ruler himself. After the exploratory archeological excavation, the experts examined the human bone remains excavated in the Royal Crypt in collaboration with several internationally recognized laboratories. The results of studies based on carbon atomization have demonstrated that some of the excavated anthropological material can be traced back to the very first period of use of the crypt in the 11th century.

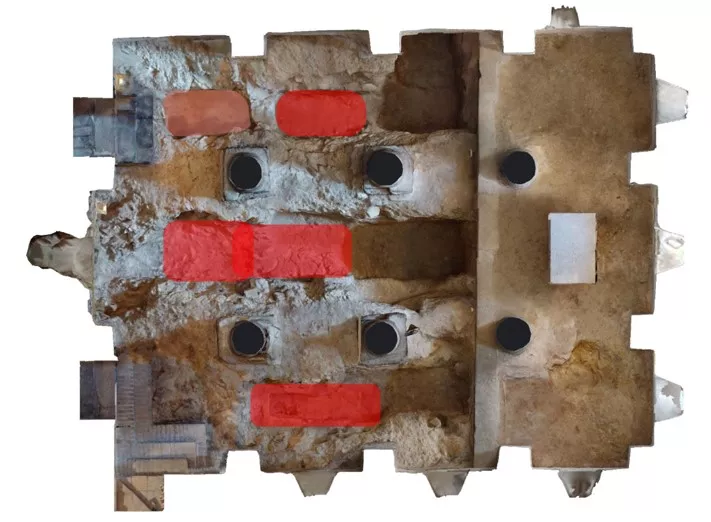

The project, entitled Multidisciplinary Research into the Royal Crypt of Tihany, was launched a year ago under the coordination of the ELKH Research Centre for the Humanities (BTK), led by Professor Kornél Szovák. The program is funded by the Eötvös Loránd Research Network Secretariat, with the support of the Benedictine Abbey of Tihany, and with the participation of experts from several institutions, including Eötvös Loránd University and the Dezső Laczkó Museum. The main goal of the project was to perform an exploratory archaeological excavation of the Royal Crypt of the Benedictine Abbey of Tihany, a goal that has already been completed. The excavation provided an opportunity to use new, non-destructive technologies. The tools of traditional archeological and monumental research methods were supplemented with complex, multi-phase photogrammetric and geophysical measurements and material tests. BTK also established a Scientific Advisory Board in order to achieve the research objectives as fully and credibly as possible. Its president is Balázs Balogh, the director general of BTK, and its honorary president is Jeromos Mihályi, the governor of the Benedictine Abbey of Tihany. Renowned archaeologists and art historians have also been invited to be members.

Extensive archaeological work in the area of the crypt was last carried out in 1953. Based on the relevant documentation, it was expected that it would not be possible to find the untouched burial in its original position on the site. As a result of the verification excavations conducted in May and June under the direction of the archaeologist Ágoston Takács, it became clear that four tombs were placed here in the early burial phase of the royal crypt. Archaeological observations suggest that no further people were buried here in the Middle Ages after the earliest phase in the 11th century. There is clear evidence of further burials from the modern period, including the Benedictine resettlement in the early 18th century, and it cannot be ruled out that the crypt served as a graveyard for the soldiers defending the castle when it was used as a border fort.

Of the four 11th-century tombs, three are located in a clear order, on the same part of the three naves, while the fourth – thought to be the tomb of a child based on its size – was built at the western end of the northern nave, not far from the other tombs. The burial sites established in the 11th century are undoubtedly aligned, but have become plain, empty tombs over time. Even so, their identification is one of the most exciting results of the research. The four tombs are not only a trace of the same era, but also an allegory for an early family branch of the Árpád dynasty.

In the charter of the Tihany abbey, the founding king, Andrew I, designated the monastery as the burial place for himself and his family. Historical science accepts the report of the chronicles, according to which King Andrew, who died in the manor house in Zirc, was buried in the Benedictine monastery in Tihany in 1060. His son, Prince David, also found his final resting place there around 1090.

As the first step of the verification excavation, three wooden chests of poor condition were excavated from the concrete sarcophagus of the tomb, opened in 1953 after a liturgy celebrated by the retired archbishop of Pannonhalma, Astrik Várszegi. These chests contained human remains held in inappropriately poor conditions and found during earlier alterations to the crypt.

Even the primary anthropological examination showed a significant difference between the contents of the second wooden crate to crates one and three in terms of the number, texture and retention status of the bones. Remains of some adults from poor condition, incomplete, and fragmented bones from box 2 could be inferred. The surface of these bones had been smeared with a lacquer-like material at a time unknown to the researchers, presumably in order to preserve them. It is also likely that the remains in box 2 included the bones that were recorded separately before the alterations that took place in the late 1890s. Accordingly, these were placed separately from the other bone remains in the stone-framed tomb of the south aisle, in front of the tombstone in what was then the south side wall. Gyula László remembered this special bone material as “patinated bones” when, in 1953, Professor Mihály Malán, an anthropologist, returned the excavated bone remains after the examinations.

Gusztáv Balázs Mende, a senior researcher at the Institute of Archeogenomics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, conducted an anthropological survey on the bone material, followed by the carbon-age dating of the bone remains. The proportion of carbon in the 14 isotopes in a given sample decreases over time, meaning this process makes it possible to determine the absolute age of organic samples. The tests were first performed in the ATOMKI-Isotoptech Zrt. radiocarbon laboratory in Debrecen, and then in two other internationally listed laboratories (Poznan and Mannheim) based on the measurement results. Based on the aggregated data from laboratory studies, it can be stated with certainty that some of the excavated anthropological material, in particular the bone remains associated with the two adult men, represent the very first 11th century period of crypt use. The results of the study also confirmed that the crypt was not used for burial after the initial phase of use. The rest of the bone remains can be dated from the end of the 15th century, while based on the radiocarbon data, most of the bones were from the 17‒19th century.

Based on the charter sources, the results of historical research so far, the historical tradition of the abbey and the results of the newly conducted archaeological excavation, the experts consider it reasonable to state that the 11th century bone remains belong to King Andrew I and his close family.

Genetic research of bone remains dating back to the 11th century is still ongoing at the Institute of Archeogenomics of the BTK. Archaeogenetic experts are confident that, in addition to the radiocarbon results, they will be able to contribute new data to the interpretation of the remains related to the royal family of the Árpád House.

A series of short films have been made about the project under the auspices of the abbey, and a larger-scale documentary is being made.

Research will continue in the framework of a new project entitled Kings, Saints and Monasteries commencing at the beginning of December 2021 with the support of ELKH.